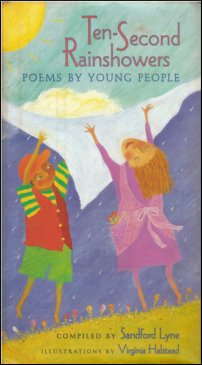

Retrospective

Sandy Lyne

Introduction to Ten-Second Rainshowers

E

arly one summer morning, when I was eight, my father woke me with uncharacteristic tenderness, softness, almost a whisper. He told me we were going out in the backyard “to hunt for buried treasure.” What could he mean? I wondered. My father was many things to me, but not a man of mysteries.

We went out to a place in the backyard near the small, converted barn-garage. There my father put into my hands a small, boy-sized shovel. He stood there silent for a few moments, surveying a scruffy patch of dirt and grass. “This looks like a good spot. Let’s try here,” he said, and motioned for me to dig. I dug for a few minutes and, sure enough, I found a dime! Excited by my success, I began to dig in another place. After a while, my father said again, “Why not try here?” Again I dug where my father pointed, and this time I found a quarter. This went on for quite some time, me digging in various places and, now and then, my father offering a suggestion: “Try here,” or “This looks like it might have something.” It was amazing how my father seemed to guess all of the places where I’d find a coin.

A few months afterward, a little older (and a little wiser), I asked my father about that “treasure hunt.” He told me that while I was busy digging in one, he’d drop a coin behind me in another place, pressing it into the ground with his foot; the first coin he had buried and marked with a stick. We had a good laugh about this. To this day, I know how my father thought of it.

I

n a very real sense, this book is the result of many successful treasure hunts, “My life is/a buried treasure/to me,” third-grader Dawn Withrow writes. “I want/to find it./I dig all day./It is very hard/to find it/all by myself.” With dazzling candor and freshness, the young poets in this collection remind us of the pure origins of poetry: the simple human need to record a pain or a joy and to know that one’s own words are more than enough.

The title of this book— Ten-Second Rainshowers— celebrates these young poet’s sudden and complete surrender to inspired awareness, insight, and expression. They get on and off the page quickly— and back to living. Like those small rain clouds that appear as if from nowhere in a sun-filled sky, raining just a few moments and then moving on, leaving behind them a great refreshment upon all things, so do these poems shower for just a few moments on the empty page—and leave for us a renewed sense of the richness, wonder, and purposes of life.

All of the contributors to this book were briefly my students when I worked in their primary or secondary schools as a visiting poet between 1983 and 1994. They came from a variety of racial, ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and they lived in urban, suburban, and rural areas. All wrote their poems in a short space of time, in the classroom or as a home assignment. Regardless of their backgrounds or educational levels, I found that most needed very few things to start writing: safe and sensible starting places, a few guidelines (for example don’t try to rhyme), and the “fairy dust” of attention and praise. Gathered together, their words represent the complex experience of childhood, evoked not as a remembrance, but rather caught alive in its own true, poetic voice.

Many of the poets in this collection, dipping their hands into the rushing stream of childhood, are startled by how quickly it is running by them, wistful that they are unable to slow its brisk charge ahead. Some simply wish a difficult childhood to be over; others are drawn by a future whose mysterious pull sometimes throws a young life into great confusion and promises something one cannot quite imagine. And still others point to an amazing phenomenon: we live multidimensionally. There is a staircase between this world and the place of our origins, and each step reaches, through experience and awareness, to the other steps both above and below it. The young poets in this anthology often play nimbly up and down the staircase, hinting at their connections to other worlds while emphasizing the need to make the lower part of the staircase, the earthly world, their temporary home. “The creek is my friend,” writes seventh-grader Scott Denson, “it talks with me by/falling over the rocks,/but the sun also/likes my friend/and likes to him/in the sky.”

I

have now taught poetry writing to over 27,000 young people. It was not a work I consciously planned for, and I marvel constantly at how it came to pass. I often remember back to that special summer morning, digging in the yard with my father. I dug up plenty of other treasures, too, that day—wonderful roots and beautiful stones, insects and grubs and long wriggly worms (which I saved in a can for fishing), an old nail or two. I found three dollars that morning and had the time of my life—and, of course, my father got his garden dug.

A few years into my teaching, I realized that my father’s invention was a universal way to reach out to young people. “Try this,” I say, introducing a new approach to making a poem. “Dig here. Maybe this will have something for you.” The treasure found is always more than the treasure buried. The implement used is a soft lead pencil. Everywhere I look, I see the garden.

© The Estate of Sandford Lyne