Spring 2012

Table of Contents - Vol. VIII, No. 1

Poetry Fiction Translations Essays Reviews

David Eberhardt

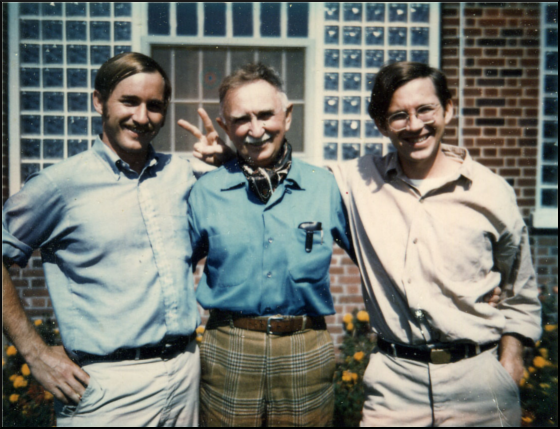

My brother, Tim, my father, Charles, and myself outside the farm visiting room at Lewisburg where I served time for an anti-Vietnam war protest. Fellow inmate, Joey, the Mafia guy, took the picture with a Polaroid. As visiting room attendant, he also dug the contraband left by visitors out of the ice maker. Thus, he had an important job (a Mob job?)

The following is an excerpt from a longer manuscript Eberhardt is writing entitled “For All the Saints”—a line from the Anglican hymn of that name, “For all the saints who from their labours rest.” Not that Eberhardt is himself a saint, just that he hung out with some. The book describes Eberhardt’s experiences with an emphasis on his involvement in the peace movement. It was 1971.

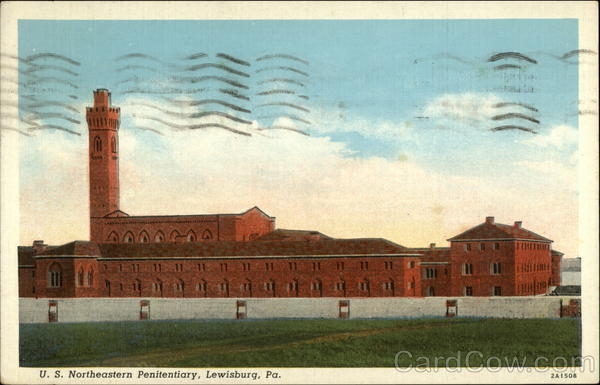

In 1967, to protest the Vietnam War, Eberhardt poured blood on draft files along with Father Philip Berrigan. Father Berrigan later participated in the more famous action of burning draft files as part of the “Catonsville 9.” The two were both sentenced to prison but were separated when Berrigan was sent to the Federal Bureau of Prisons facility at Danbury, Connecticut, where he joined his brother Daniel, a fellow participant in the Catonsville 9’s anti-war action.

The excerpt picks up just as Eberhardt left the main prison at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania and went to the nearby “Farm Camp”, a far more bucolic setting than the main prison.

The din and roar of eventful current that had swept me up for four years subsided as I moved to the Lewisburg Farm Camp. I was able to relax a bit from the landscape of issues into a landscape of interesting human faces, my fellow cons. My first job assignment was an easy one: wiping up tables in the dining room. My co‑worker, Joey, who had also just arrived from the wall (the main prison), needed light work: he had entered prison with four bullet wounds to the stomach and they weren’t draining properly. He was a Mafia man and Carmine Galente was showing him around. The two approached me, Carmine fingering the required Mafia De Nobili cigar in its holder: “Nowa Joey, dis here’s Ebahart and uh Ebahart I want yuse to make it easy for Joey here, uh, he’s got bad health and Joey dis here’s a good kid and he’ll show yuse the ropes, he’s one of tha Berrigan gang, you know, da priest and dem nuns and so fort...” “Yeh, da fadder,” Joey says devoutly, “ain’t it a shame.”

Another mobster, J, who lived in our eight‑man dorm, was a charming old guy, so used to the big spender role on the streets that the inconveniences of the farm life incensed him: the food, the work, etc. He didn’t like his assignment at the power plant, so would find some nook in which to read because of his “bad back”, or he would parlay many trips into the wall on hospital sick call so he could communicate with friends. Or he would spill coal and misread meters. It was all fairly nonpolitical but it amused me, and one day I pointed out to him the similarity between his actions and ours—of non‑violent resistance and civil disobedience. He understood. He made himself into such a nuisance that he achieved a transfer to one of the plummiest positions of all, attendant at the prison gas station. Very few trucks stopped there and you could play gin rummy all day. J ate upstairs in our dorm or in Carmine’s room from their own private stock of smuggled goods: pasta, salami, anchovies, etc.

Because of his truck‑driving skills, a black inmate, Doc, was prison fire chief. The fire truck for the main prison was housed at the farm camp and I volunteered to join the six-man crew. It was a desirable position since we got to take test drives around the perimeter of the institution and occasionally go outside the prison to train with local fire crews or put out some nearby fires.

We did some training with the local Lewisburg Township Fire Department—a sharp outfit. I waxed quite poetic about them, since they were, I believe, unpaid volunteers. I thought of the anarchist societies proposed by Prince Kropotkin which would be based on mutual aid, as I sat and chatted with them amongst the snorkels and oxygen masks, the great yellow hoses and bright shining red trucks. One of the grumpier older inmates on our prison crew—a “conservative” I guess—questioned my right to take part.

What if we got a fire at a draft board or at a ROTC building (maybe at the nearby Bucknell College)? I wouldn’t try to put it out and might endanger his life, he reasoned. His objections were farfetched to the others, however, since they figured we wouldn’t be called to many such fires. I got into some interesting discussions with the town firemen about burning draft records. One said he thought it would be O.K. as long as we took the files out of the building!

Checking hoses and equipment on the other side of the main prison next to the placid Buffalo River was a treat. You could open the hose nozzle wide and pound the river with a hard jet of water or turn it to its narrowest setting, “spray, curtain, mist”, in which case the fine spray would steep Hamp’s kinky black hair in silvery dew balls. (Doc’s last name was Hampton.) I wrote a poem about it. Prison was great for reading and writing and meditation—a Zen practitioner’s dream.

The crew joked about a possible prison fire and the political issues it would present, i.e., should we help put it out? After all, prison fires were usually set by our fellow inmates. Luckily, we never had a bad prison fire. The only one we were called to inside the wall was a very small one in the Education Department, probably the work of some disgruntled scholar. It was out by the time we got there. As we uncoiled our hoses under the Warden’s worried gaze, one of the gas mask boxes fell open and out spilled someone’s stash: tins of paté, canned shrimp, Vienna sausages, and other wonderful delicacies!

We jokingly appraised each situation as to possible “good days” or days of credit off our sentence that we might earn. One inmate claimed to have thrown the Warden’s dog into the Buffalo River so he might rescue it and make parole. Prison was full of such amusing “games”. Once we were called to a fire at the Associate Warden’s house. Hamp had never liked this particular prison official, so he took a very circuitous back route, driving very slowly at about ten miles per hour. Luckily for the Associate Warden, the town crews had already arrived.

Once we were called to a brush fire up on Dale’s Ridge overlooking the far blue Allegheny mountains. With them in front of us and the institution far behind, in the sweat of the work under heavy yellow slickers and in the pungent cedar and pine smoke, spiritual feelings rushed over me, all mixed up in calm and bliss and sexuality and sadness as I thought of the nearby Susquehanna and Buffalo Rivers, flowing gently. The cedars can burn explosively like an oil fire, a fellow fireman told me; I imagined this happening.

Between us and the mountains, the ridge dropped off precipitously and deep and I thought of the long geologic maneuvers which formed it and the valley below. This was a sort of epiphany—being in this moment—about as good as it gets, the kind of moment we live for: unpredictable, unplannable, a moment that would well up again in my memory the way moments do all down through life, making life totally worthwhile, with no assistance from anyone else. . . . emphatic, necessary, hieratic, vatic, oracular, the kind of memory you fondle and embroider and lie about and make poetry out of.

Such memories are all the wealth we need to survive (besides food and shelter in bad climates) . . . . and, don’t forget—political struggle.

Don’t let me make imprisonment sound too “nice”. This was 1971—the year of the prison rebellion at Attica—it was the year that George Jackson was murdered in California. Phil Berrigan saw prison as a place to be in to unite with the poor and downtrodden and I recommend the experience (at least here in the U.S.) for the callow youth of today. Being imprisoned in Syria would be no joke. The point is: take some action and take some risk!

The many pheasants in the corn fields around the farm also presented romantic images. Hunters couldn’t follow them onto the “reservation”. Inmates were allowed to trap them and put them in crates for shipment to sparsely pheasanted parts of Pennsylvania or maybe to the banquet tables of federal prison officials. If you were on one of the outdoor crews, you might stop to visit the pheasants in the tractor shed and admire them peering glum but fierce from between the slats of their little imprisoning, lobster‑trap crates. You would especially notice them in the fall when the corn had been cut. The burningly phosphorescent males looked like freedom as they scooted up out of the corn stobs with a whistling sound to escape you. Their iridescent vests for courtship displays like pigeons’ or the blushes of purple tetra fish reminded me of my sexuality and how much I missed Louise. Or they reminded me of beautiful privacy and meditation as they flew up evenings to roost in skeletal trees.

Always they were gorgeous with strange autumnal hues: coppery chests with freckles like those in the tubes of iris flowers or like the shimmering markings on an eye’s iris. They had white rings round the necks. . . which inmates dearly loved to wring. They were delicious cooked between the rungs of our radiators. (Prisons are kept hot; lethargy results.) To feather, gut, joint them, it helped to know someone in the butcher shop.

Winters the pheasants would sometimes make the mistake of flying over the main prison wall to look for food on the ground, over steam pipes where snow had melted. Supposedly, an inmate had caught one from his cell window by dangling a pin, bent fishhook style, on the end of a line. I imagined the raucous squawking in the clear blue Pocono air!

Mornings we dozed toward winter on our work crew in the general farm shed. The work of the year was largely done, the root cellar filled to capacity with apples and potatoes. Zillions of snowflakes blitzed the surrounding fields until they looked like the flakes of sugar-frosted cereal. The snow wiped out our vistas of the far blue mountains. We could only see the minute details of the close black and white land looming bitterly larger and larger. We could feel the full weight of our unjust sentences. . . time itself an unjust sentence!

Did we deserve this? We were almost tricked to wonder, the slave’s terrible question. Had we not chosen to be here? Wasn’t this our fault? We would interiorize our sentences and grow to accept them, a final brutality, as the snow came in on a slant over the Alleghenies, beauty and horror together. Luckily, we war protesters were not alone, we had loved ones and vast support systems. Christmas brought us cards from all over the world, even North Vietnam, as I remember it. We had belief. We had humor. All these things enabled us to be sarcastic and angry. We would never become “losers” like some of the regular cons, for we knew our mission, we knew who we were. Society might despise us, but deep down it knew we were right (or did it?).

We took our place beside the “common” car thieves and bank robbers. Pheasants are so dumb they will enter a wire cage trap, unable to retrace their steps out of the little hatch to freedom. Society stands behind the prisoner smugly saying, “You have seen this happen to a person also.” Undoubtedly many of the inmates would return to crime upon release, as we all return to the ruts in our mind which are familiar. But we not only knew the way back into society, we rejected it. And so, in a way, we were free.

Such philosophizing, writing it down, playing pool or the piano or guitar helped me pass the time. Story telling was a well developed pastime. Jesse, an elderly, earthy, illiterate black man from Baltimore, regaled us with some of his favorite tales as we sat out cold fall days in a farm shed after the potato crop was in. He had killed a Chinese fellow at a restaurant in Washington, D.C. and complained that no “chink” was worth all the time to which he’d been sentenced.

Once he was in a bar on Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore and had finally located a choice whore for the night’s entertainment. She was a darling, all in satin with gorgeous, mincing feminine ways. He took her to a hotel downtown and wanted to dispense with preliminaries and get right down to it since she looked so fine. So he asked her to take off her clothes. “Well,” she said, “first let’s turn out the lights.” He wanted to watch her undress but she kept insisting, so he turned off the light and they proceeded to bed. Next she wanted him to undress her piece by piece in the dark as if. . . as if, he began to get the feeling she wanted to hide something from him.

“Aw, have I got myself a queer?” he began to wonder to himself. “Well. . . well, was it?” we all burned to know. Then he felt that hard thing between “her” legs and he knew. . . “Good Gawd almighty!” “You went on ahead anyway?” someone asked him. “Damn right, I wasn’t gonna miss out on those, get me a taste of those “cakes”. Another story of Jesse’s was his “with or without the dog” story. Jesse goes to a whore house; it appears to be one of the nicer ones with lots of girls to choose from, so he goes upstairs with this lady and when they get into bed she asks him does he want it “with or without the dog?” This confuses him but the place seemed pretty special so he told her “with”. She went out of the room, then came back and they got down to business. All of a sudden in runs this little poodle and commences to fuck Jesse in the ass. “I jumped so hard, I ran my head up against the headboard and my head was bleeding. I’se so mad I jumped up and kicked that little dog halfway across the room!”

Catonsville 9 member Tom Melville had wonderful tales about the Mafia mobsters Tony Prevenzano and Carmine Galente. Tom had had considerably more of a relationship with Tony and Carmine at the farm camp than I had.

Tom described a committee formed for a Memorial Day picnic consisting of himself, a Jewish lawyer from Ohio, and “Tony Pro”. Tony had a reputation in prison and was accorded respect by the other prisoners. Tom told us that he tried not to look Tony directly in the eye. The Feds had allowed the committee some leeway. They were authorized to choose whether it would be hot dogs or hamburgers for the picnic. The Jewish lawyer piped up that he had researched the matter somewhat and that the general feeling among the prisoners was for hamburger. Tony glared at him icily. He then picked up one side of the table where they were meeting and upended it, squashing the lawyer underneath. “We’re having hot dogs, and don’t you motherfucking forget it!” was his rejoinder to the lawyer and that was that!

Once Carmine drew Tom aside to complain, “How come there aren’t Italian bishops in the U.S.? How come it’s always Irish? Huh? The motherfucking Pope is Italian. Where’s the Italian bishops?” Tom said that Carmine always criticized at the top of his voice and what he said, went. He kept younger Italian mobster types in strict control. Tom had heard him screaming at one unfortunate fellow con that Italians must never be caught playing handball with the “niggers”, they must only play with fellow Italians.

Tom’s best Carmine story he called the story of the “Irish Mafia”. It seems that Tom had taken on or been assigned the duty of movie picture director. Always the front couple of rows in the movie room were reserved for Carmine and his retinue. But, in a playful mood, Tom had decided to play a little joke on Carmine and, having arrived to the showing of a film before Carmine, who could afford to wait until the last minute, Tom took a seat right up in front in one of the sacred rows. The loud bantering and exchanges that always preceded any gathering of cons stopped immediately and in hushed whispers the other cons debated what might happen to Tom for this transgression. One of Carmine’s men came on the scene, a forerunner to the main Carmine group, and seeing Tom in the row, accosted him in shocked tones, “What the fuck are you doin’ here?” Tom told him thoughtfully to tell Carmine that the Irish Mafia had arrived. “The Irish Mafia,” the runner asks and runs off, doubtlessly thinking that Carmine will have to deal with the new challenge ruthlessly. Carmine arrives and comes up to Tom, looks him over and starts to chuckle. “You!? You is the Irish Mafia, this is the Irish Mafia?” Carmine pauses for a moment and then addressed the entire gathering. “From now on,” he says, “dese front rows are reserved for the Irish and the Italian Mafia!”

One time, Mob boss Joe Salerno was observed on the evening television news as he was being interviewed in New York about the very subject of the Mafia. Salerno was complaining to the reporter that the term “Mafia” was discriminatory and that the more respectful term of Italian‑American would be correct. Carmine jumped up enraged and poked a finger at the screen. “We’re gonna get you when we get out, you cheap no good sob motherfucker, we’re the Mafia and we’re proud of it!”

© David Eberhardt