Fall 2012

Table of Contents - Vol. VIII, No. 3

Poetry Fiction Translations Reviews

Barrett Warner

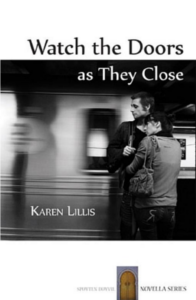

Karen Lillis,

Watch the Doors as They Close, ISBN 978-0923389871, Spuyten Duyvil, 2012, 100 pages, $10.00.

In most bookstores a big fat spine—not its cover—sells a book off the rack. In the electric marketplace books with anorexic spines have experienced a renaissance. The return of the chapbook and the novella reward the reader with exhilarating fast tempo literature. One page promptly informs the next and builds a tumultuous crescendo. Karen Lillis’ novella Watch the Doors as They Close is a fantastic nail-biting, lip-chewing read. It’s a love story full of smashed hearts, cursed knowledge, life’s chaos and nostalgia, and an ominous political back story. The mood is dark. You’ll need a flashlight as you feel your way around this story of a Brooklyn bookstore clerk’s relationship with Anselm, an Appalachian savant who descends from suicides, coal mine accidents, farm work and opera.

Lillis’ narrator has already written a novel while Anselm is a composer who concentrates “on hearing the noises in his head and writing them down.” His head. “Sometimes when he was thinking out loud his fingers started playing piano keys that weren’t there.” Anselm is deaf in one ear and mostly deaf in the other. He has little interest in hearing music or playing it. For him the search for truth and beauty is a process of inventing patterns. Not surprisingly, Anselm’s former girlfriend is a member of Mensa and “programs databases for a living.” These early notes clue the reader into an important subtext for Lillis—the head, knowledge, awareness, consciousness—and how little any of it matters to true emotion, to “heart energy.” Thinking versus feeling affects the narrator’s ability to cope with such a grand prospect as love. She struggles to understand an irrational idea, a genuine feeling, something that may have happened as if love and imagination were a lot closer to heart energy than geometry.

The narrator uses hedging tones throughout her tale of woe: “I’m not actually positive…I’ve just put it together from context clues,” “This, I believe,” “If I remember,” and “I didn’t even know enough to know what questions to ask.” Her role reminds me of Joseph Conrad novels, where a man of great seasoning narrates a tragic story of youth, except that in Doors the speaker and the protagonist are the same person. Lillis presents her novella, the story of a six month romance, in the form of journal entries or letters to herself over a seventeen day period so that it feels like memoir and epistolary novel together. This is where the epic poem meets the quotidian.

Lillis’ Anselm is a chameleon, disguised by time of day, good space, and “bad space.” He’s desperate to cover up a past which he cannot escape while at the same instant he idealizes his origins. His mountain mama home life, his school days at Oberlin, his project for a song in New York—these environments become his moral compass for periods of time but his true north always has two fingers crossed behind its back. Something simple such as having an egg with his lover is impossible. He cannot eat eggs because they remind him of slaughtered animals lying around where he grew up. He can’t go to baby showers because babies make him think of eggs.

The reader sees past this deception while being charmed by its cleverness. The real truth is that if his lover wants to go anywhere he won’t want to go. That would make it feel like a date. It’s his way of controlling every scene and manipulating her guilt for dessert. And yet, for all of this, he loves. And the narrator loves. Until here we are, the narrator “fully committed to the thought of him” and we’re only on page thirteen.

Reading this book I felt the wind right on my face. My advice is to wear gloves; heat is coming off each page. Lillis writes: “Anselm was good at promises. I was good at hoping for the future, hoping and waiting for his promises to come true.” Her narrative style mixes abstract memory and desire with hyper-realism. She records each new slant of a phone call, or an evening, but without repeating herself. The narrator’s sense of time is associative, not transitive so that her story doesn’t move across the calendar but instead hovers around clusters of feelings set against the back story of a nation declaring a war on emotion, terror. The action is conveyed by discovery, and Lillis is careful enough to leave us new wonders at every bend. Our only chance to breathe is the half-second needed to turn the page.

Lillis’ country mouse and city mouse fable builds when she goes Bible on the second day, taking on the story of Adam and Eve. It’s as if all of creation came down to the problem of loving and thinking and dodging or clinging to the forbidden fruit. She writes: “I suppose the strong instinct to write a tell-all comes from Catholicism…in the world outside the Church, to sin just means to experience...

I wonder if anyone besides confessing Catholics or people who’ve betrayed someone knows what I mean. Well, sure, you can hardly make it to age fifteen without hurting someone you love and regretting it terribly. But this feeling -----I can only barely touch it from here. Such an intense longing to love and feel love as you once did as a child, ignorant of what lay ahead, ignorant of the limits and disappointments and the rejections and the pettinesses that dwelt inside even the nicest people. The longing is to feel such a purity, such an intensity, along with the knowledge you’ve gained in adulthood. Wasn’t that Faust’s dilemma? Adam and Eve? The Taint of Knowledge?

An omniscient narrator who rejects knowledge? Quite suddenly Lillis’ love story takes a turn for the nouveau roman for hers is a narrator at conflict with her own voice. The motion takes a wheeling, circling direction. It makes you want to shout encouragements to her as you read. Every plot point is reduced to her shuddering, scared and shaky loneliness, her questions who am I and why do I exist? Anselm will not answer any of them. Who or what is the force inside him? He’s arrived in New York City from Pennsyltucky early on September 11th. During their romance there are power black-outs affecting New England and Canada, ferry crashes, tenement fires. Lives are lost and manuscripts burned. At one point the narrator fears for her own life, believing she may have fallen in love with a serial-something. In this way Lillis depicts a kind of sordid day-to-day Apocalypse in which the realest moments take place on a futon in a small room whose occupants—the lovers—only vaguely sense that eviction looms.

Sounding a little like Cotton Mather, the narrator reports: “In the beginning, it was him telling me, I love the way you’re so aware of your own becoming. You’re always fluid, in motion.” Anselm woos the narrator who feels she isn’t moving at all and is “stuck on life” and mopes around “this place of stagnation where one expects life to be so dynamic.” She doesn’t even trust what she knows about herself. This scene occurs in a two-page chapter that begins “Anselm’s favorite insult was disingenuous.”

Anselm is a remarkable achievement in character portrayal. The Bohemian nuance to their existence conjures Hemingway, but Lillis has much closer ties to Papa. For years, writers have been personifying death, turning death into a character that called on you and you it, a character that followed you, and whatever other clichés you may wish to add. In Hemingway’s Lady Brett Ashley (The Son Also Rises) Hemingway personified life, rather than death. When he wrote, “She had curves that could rival the hull of a racing yacht” he was saying life had those curves. The tension is Jake Barnes, seeking life, falling in love with life, but unable to possess life because of the deadness inside him. Lillis’ Anselm is Life. “Everything flows,” he says, often. “Life flows.” Anselm flows. He can be enjoyed but not loved. He can be experienced, but not possessed. The narrator observes: “The longer he stayed away (the longer life stayed away), the taller our dreams soared and the more dangerous we became to ourselves.” It’s as if dreams are the bridge between the dying inside all of us and the life we hope for, the life which makes promises to us which never come true. In the face of this heartbreak sometimes we feel anger, but “anger is a mask, numbness and depression another level of masking.” Anselm, too, is controlling, just like life: “he wanted to please a woman in order to conquer her.” Ironically Anselm—life—was so “skittish among the living.”

What’s so magical about this book is that we know not to trust a character like this, an ego-maniac with low self-esteem, but Anselm’s so life-like we feel we must. I loved the quiet way the narrator determinedly and graciously takes back control over her own life until by the end she’s almost defiant, alone, but alive, a survivor of fantastic romantic peril, having come to realize that life is not perfect. It hasn’t any answers for us at all. She even digs into her wallet to pay for the cab life takes to the train station when it leaves her. Life is so messy that way. Life has its wounds. And we cannot clean it up or make it better no matter how big we make our hearts.

Oh but the trying and longing for it to be otherwise. Wouldn’t it be nice to think so?

© Barrett Warner