Winter 2011

Table of Contents - Vol. VII, No. 4

Poetry Fiction Translations Reviews

Barrett Warner

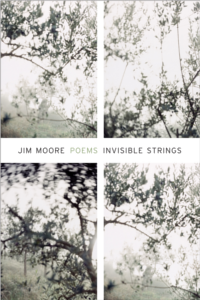

Jim Moore,

Invisible Strings, ISBN 978-1-55597-581-4, Graywolf Press, 2011, 96 pages, $15.00.

Sometimes a gene will skip a generation and show up in a grandchild. Sometimes a gene will skip five generations before revealing itself. So it is that pre-World War I imagist poetry makes a return visit in Jim Moore’s new collection, Invisible Springs. Called “jagged” and “haiku-like”, Moore’s poems are neither. Their brevity and impressionism make the larger, abstract ideas of ruin, death, loss, love, and companionship which they’re set against seem all the more terrible and gratifying. Most are written as clusters, or titled stanzas within a four or five “stanza” piece. And the poems go back and forth, grouped into multiple sections of St. Paul, Spoleto (Ity), and America so that the reader feels he is constantly taking off and landing. In fact, the book’s title comes from a crow doing just that: “...see a crow/ rising into thick snow on 5th avenue, as if pulled by invisible strings.”

Mark Doty has said that a good poem title is any that does not harm children or animals. Moore’s titling agrees loosely with this premise, but his titles are essential to the form of his poems. When the title is also the leading line he moves directly to the poem, relying on the break between the title and first stanza. When the title does not serve as the first line, the first line of each poem is a one line stanza. Even short poems need to breathe, and Moore is careful to get plenty of air into his. Consider section 2 of “Love in the Ruins”:

leaves his lover’s house

to go back to his basement room

across the alley. I nod hello,

continuing to pick

the first small daffodils

which just yesterday began to bloom.

“Love in the Ruins” begins with a reminiscence over his dead mother folding the table cloth “so carefully,/ as if it were the flag/ of a country that no longer existed,/ but once had ruled the world.” The second part is given above, an intimate look at stealing intimacy. In the third a helicopter flying overhead conjures memories “of that old war/ where one friend lost his life,/ one his mind,/ and one came back happy,/ to be missing only an unnecessary finger.” There’s a political connection between the folding flag of the previous generation and Vietnam in the first and third clusters, while the second and fourth clusters are joined by intimate portraiture. The fourth section similarly involves catching an intimate moment, this time the crow drawn into the snowy sky, the daffodil pickings off the ground, the crow lifting, lifting into the blizzard of life, rising out of ashes. The paired stanzas representing the big political world and the small intimate spirit world sort of go against each other. Unless of course you’re writing about the messiness of life which Moore takes such pleasure in. Let’s have a keyhole peek at his fifth cluster to see how he resolves things:

another winter: my black stocking cap,

my mismatched gloves,

my suspicious, chilly heart.

Well it might be chilly now, but there are flowers rooted in that old heart and not all of them are mal. In his poem “Almost Sixty” he writes “everyone at the party/ younger than me/ except for one man./ We give each other the secret password.”

There’s your bloom, Mr. Moore, there’s your daffodil.

What I like in this collection is that while form is almost everything, it is also merely form. Yes, Moore likes the breather between the first and second lines. Yes, he seems to have issues with justifying his left margins, giving his stanzas a dented look. But Moore allows himself a good measure of caprice in his line length, his meter, the amount of words he uses to target a truth, and so this is where his form becomes lyrical. In section 1 of “Trying to Leave Saint Paul”:

that lead nowhere. One of them

ends where quiet drunks sit

in old September grass

on top of a hill.

Street cars used to run here,

through a tunnel cut into a hill.

The sun rides so low

in the cloud-filled western sky,

it makes the empty bottles glow.

It is hard not to imagine this setting in any city, whether on the Chesapeake or Lake Superior. Roads leading nowhere and at the end of one of them, a pile of drunks sitting on “old” grass, the street cars that no longer run and now the sun setting, riding as if on the rails the street cars had once used, and still it makes the world beautiful, this light that makes anything possible when your bottle is empty.

Dave Smith,

Hawks on Wires, ISBN-13: 978-0807142318, LSU Press, 2011, 94 pages, $18.95.

“Stayer”

Horse races used to be twelve mile affairs, with a water break every four miles. Today’s classic races are a mile and a quarter. A “stayer” is any horse that can get a mile. Dave Smith’s twenty-fifth book, Hawks on Wires, just out from LSU Press, puts him in the old school of racing. This one is a stout, professional stayer. And just as others are leg weary and stumbling about he gives us a surprising turn of foot that takes us to the wire as if God is on his back and the devil is at his loins.

Dave Smith’s belly may have gotten a little soft over the years, but he’s made up for it by being sharper, wiser, craftier. “You don’t get to be my age for nothing,” he seems to tell us. Forty years ago Smith was the next great writer out of Virginia, tall and handsome with sporty long hair and crunchy mien. Some meet friends in the lobby and others in the alley but Smith met his friends roaming the woods just north of Tidewater’s “Dismal Swamp.” Big on environment, big on the outdoors and big on the mystery of place, Smith was the “go-to” poet for do-it-yourself nature types with social conscience. It’s important reading Hawks on Wires to consider Smith’s early years at the mouth of the Chesapeake. After a lifetime wrestling the poetry beast around North America he has been moored the past ten years in Baltimore, at the opposite end of the bay, where he has taught in the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars. Much like his two salty-air forwarding addresses, these poems spur the opposite ends of his life. Even the title poem was drawn from his many travels back and forth, Baltimore to Tidewater, to visit his ailing mother, his words wrought in a forge of devotion and restlessness.

Smith’s poem “Early Bird Dog Training” is an intimate look at coaching “headstrong/ pup who makes my arm twitch with fatigue” and later, “Ten months now, he hears every bird the same.”

I don’t know his limits, so leash his desire’s

worst, though he bucks and huffs and whines. Heel, heel,

I bark, acolytes metering a suburb’s field.

Until he’s caught by a goldfinch. Is this it? –wild

canary, butterfly yellow, that flits, scolds,

Seaming the beaten path with beauty’s signal.

How bold, notes from a hidden branch that trembles!

Yet I can’t find the nesting tree, nor can dog,

who, unmoved by form, points not song but log.

This is a poem for M.F.A. candidates, not juvenile bird dogs. It is written for we young poets hearing every bird the same, bucking and huffing and whining, limitless, needing to have our worst desires leashed. Smith wants to urge us here and there but doesn’t want to take our heads away as he helps us learn the value of discernment. In Smith’s poetry there is a triple helix comprised of an extended metaphor, some narrative thread and the music of the words and lines. At times one attribute leads to another. Positions are switched, but all three strands finish together for this master poet. Smith’s verse forms, his more or less balanced meter, couplets, and end-rhymes, mask how the story of the poem feels informal and jotted. The opening line, “July day walking Finn number two headstrong” feels more like a note to self recorded in a work journal by someone who doesn’t talk a lot. The penultimate line, “Yet I can’t find the nesting tree, nor can dog” humanizes the narrator. While he’d like to see himself as the all-knowing guru, Smith is caught up in the same mystery as his student Finn. Even Smith puts in a little huff and buck himself at life’s surprises!

The power of experience means nothing without the power of words. In “Colored Store” Smith writes: “So I’d say it, too, trying to learn how/ words manage men, and meant/ I’d have an answer one day…and me/ hot mornings in the South fifties, sixties/ salted nuts like blisters on my tongue./ Drank Pepsi, said nothing at all.” In a poem, “Sawmill,” set in the time that Smith was a student, he’s also coaching the young of us:

among the toe-scuffing of the old ones, who, before me,

boys, waited here, smoking, talking of women they’d touch

in low whispers, then all week rise, work, and walk out

the clay road with the odor of wood on them.

There’s a lot of action in a Smith poem. His subjects tend to run, pant and sweat. Even his diner poem has a waitress on wheels. “Skating Waitress at the Circle Drive-In” also reveals Smith’s excellent use of compound subjects in a sentence, as well as compound sentences within his stanzas. It is nearly impossible to “point” to any one subject as marching the line forward: “Who never was stabbed, or struck, or rose up to say/ Fuck you to that ass skating away, to her pimply cheeks/ sucking in, out, to the gum-chew, rat-hair the sailors cried out for.” Subtract too the use of pronouns and noun articles: “as real dinner where we sit, wife, me.”

Where does our eye find a place to rest? We focus on the one moment of the poem that Smith calls the “gift” as in the line, “Gift of the little muse, whooshing circles, tangents, like words.” This poem, “A Gift Boat” is also written for poetry students:

quoter of Coleridge, brought me to the strange craft

a wild storm, fizzling out, left in the march. She shrugged,

a few rules out there. “You want it,” she said. “It’s yours.”

Smith does want it, both the boat and the metaphor it represents. For that’s what he’s saying to us, the wanting and the journey and the work all go together, no matter how simple or complex our constructed stanzas. The great surprise of this book is the way Smith weights experience over concept without reducing his lived moments to disorderly confessions. All of which could make Smith seem like a relic of bygone days. Not so, this man has a lot tell us about our world today, as a poet and an elder. For that’s what these poems are, campfire tales passed from older to younger, with too much advice no doubt and lots of blandishments and so one sometimes thinks, oh grandpa, not again. Yet still, reading him, I wouldn’t trade him for the world.

© Barrett Warner