Fall 2011

Table of Contents - Vol. VII, No. 3

Poetry Fiction Translations Reviews

Allan Roy Andrews

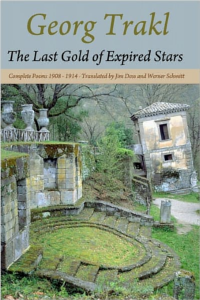

Georg Trakl,

The Last Gold of Expired Stars: Complete Poems 1908-1914, Translated by Jim Doss and Werner Schmitt. Sykesville, MD: Loch Raven Press, 2011.

The subtitle of this dual-language volume tells many readers why they may never have heard of Georg Trakl: the collection of his complete poems spans a mere seven years; nevertheless, Trakl, an Austrian poet, ranks among the most important of the Expressionists, a group that flourished in German-speaking countries during the years prior to World War I.

These artists focused on impressions and suggestive images communicating individual, subjective experience, often capturing the human experience of Angst—a German concept that conveys a deeper, often crippling, life tension not easily communicated in the more clinical English translation, anxiety. The angst of which Trakl writes was perhaps most famously depicted in the 1893 influential painting of the Norwegian impressionist Edvard Munch called “The Scream.”

Trakl, whose poems are suggestive pieces depicting a subtle, more spiritual anxiety related to death, melancholy, and depression, seems to encapsulate the experience of lamentation. Consider this shortened version of a rondel:

Flown away is the gold of days,

The evening’s brown and blue colors,

The shepherd’s gentle flutes have died away,

The evening’s blue and brown colors,

Flown away is the gold of days.

Trakl’s poetry began appearing shortly after the turn of the 20th century; his first published poem came in 1908 when he was 21. In less than seven years, his career ended; he took his own life with a drug overdose in 1914, just three months short of his 28th birthday.

Never a particularly good student, Trakl began experimenting with drugs in his late teens. His life for the next few years focused on becoming a certified pharmacist. During this period he wrote unsuccessful plays and eventually served in the military with the medical service, a position that apparently provided him with easy access to materials that could satisfy his addiction.

During these years his poems became increasingly noticed. In 1914, he was selected to receive a grant for needy artists from the philosopher-theologian Ludwig Wittgenstein. World War I broke out, Trakl never received the money, and was enlisted again in the Austrian Medical Service. Following a battle at Grodek (Eastern Poland) in September of 1914, Trakl, in anguish over the wounded and dying he was attending to, attempted to shoot himself and was hospitalized in Krakow for treatment of his mental anguish. Two months later he succeeded in taking his own life with a cocaine overdose that stopped his heart, just a brief time before Wittgenstein came looking for him in Krakow.

One of Trakl’s best known poems, published posthumously, is simply entitled, “Grodek.”

In the evening the autumn forests resound

With deadly weapons, the golden plains

And blue lakes above which the sun

Rolls more somberly; night embraces

Dying warriors, the wild lament

Of their broken mouths.

Yet silently in the meadow

A red cloud, in which an angry god dwells,

Gathers spilled blood, lunar coolness;

All roads end in black decay.

Under golden branches of night and stars

The sister’s shadow staggers through the silent grove

To greet the ghosts of heroes, the bleeding heads;

And quietly the dark autumn flutes resound in the reeds.

O prouder grief! you brazen altars

Today an enormous pain nourishes the hot flame of the spirit,

The unborn grandchildren.

If Munch’s art can be said to culminate in a scream, it can be said that Trakl’s poems culminate in a whisper.

With gentle expressions, Trakl, who lived his brief life in the chains of mental anguish and pharmaceutical dependency, sought light through the wormhole of melancholy and wrote from the hellhole of addiction.

Dark stillness of childhood. Under greening ash trees

The meekness of the bluish gaze feasts; golden repose.

A dark shape is charmed by the fragrance of violets; swaying ears of corn

In the evening, seed and the golden shadows of gloom.

The carpenter trims the beams; in the dusking valley

The mill grinds; a purple mouth swells in hazel leaves,

Masculine bent red over silent waters,

Autumn is quiet, the spirit of the forest; a golden cloud

Follows the lonely one, the black shadow of the grandson.

Ending in a stony room; under old cypress trees

The nightly images of tears are gathered in a well;

Golden eye of the beginning, dark patience of the end.

Trakl’s poems are tinged with the argot of Christianity: a glimpse at the glossary that Doss and Schmitt compile for this volume underscores such allusions. Found in Trakl’s short-lived portfolio are these spiritual terms: All Soul’s Day, Angelus, Azrael, Barabbas, Cain, Confiteor, Crucifixus, De Profundis, Dies Irae, Eden, Elai, Exaudi me, Golgotha, Hill of Calvary, Jerusalem, Jesus Christ, Kristus, Mary, Mary Magdalene, Mount Calvary, Pharisees, Pilatus, Psalm, Rachel, Rosary, Sabbath, Saint Thomas, Saint Ursula, and Sea of Galilee.

One of the minor disappointments of this volume might be its failure to provide a similar glossary in German. But that nitpicking critique does nothing to detract from this fine collection (which, incidentally, includes several of Trakl’s letters, aphorisms, and dramatic fragments, as well as a valuable chronology, a biographical sketch, and a cache of photos of the poet’s family and friends).

Doss and Schmitt have provided what can easily be called a definitive and exhaustive volume of Trakl’s poetry, and their inclusion of the original German versions should make this book an academic standard for those who do not handle German but seek to know this quiet and distraught expired star of Austria.

© Allan Roy Andrews