Spring 2010

Table of Contents - Vol. VI, No. 1

Jim Doss

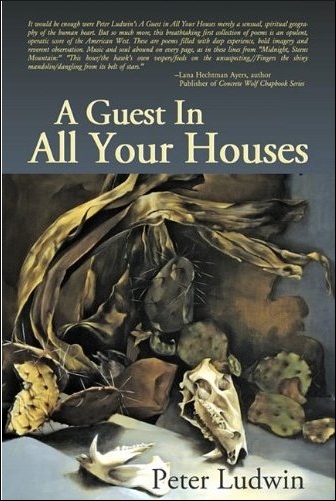

Peter Ludwin,

A Guest In All Your Houses, Word Walker Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0578003900, pages 89, $13.95.

Henry Ford once said: “History is more or less just bunk.” Thank goodness Peter Ludwin didn't listen to him. History is like an unseen ocean washing over the pages of his debut volume of poetry, A Guest in All Your Houses, shaping his landscapes of prairies, the desert southwest and Mexico, washing over the people that populate these pages, subtly influencing them in ways they don't even understand. History is alive, like the bones of ancient buffalo that rise up from the roots of prairie grass to plow the wheat and corn fields of the Midwest, the songs of the Anasazi that still echo through the red rock canyons, or the faces of the conquistadors that peer through the features of the conquered.

The book is divided into three sections: Compass Points, Four Corners, and Fugitive Kind. Ludwin fills each section with narrative poetry that stitches the past and the present together into a quilt of many colors, many meanings, a checkerboard of characters and events that pull the reader sympathetically into his world. One of my favorite pieces in the book illustrates his seemingly effortless gift at creating a multi-textured, multi-layered poem:

Driving east, you smell Kansas

before you ever reach it,

the stench of feedlots

like faded, splintered wood

that warns of poisoned drinking holes.

After this: corn, wheat, silos, water towers,

flat horizons of domesticity

raising young Republicans for Christ.

When you find, somewhere between

Wichita and the Missouri border,

a few swaths of bluestem prairie,

all that simply blows away

like lives caught up in a twister.

Shaken, you stumble over debris

brushing pigs and Protestants

from your hair, wonder about the origin

of the river that now carries you

through a pack of mating wolves.

This is what the grasses give you:

the owl you reclaim in the mirror,

the night wind wooing its tail.

The quickened pulse, the stalks

whose rolling swells contain it---

what do they reveal but the profligate

licking his self-inflicted wound?

The voice he strains to hear

stuffs its own mouth with carrion,

the severed cry of the dung beetle.

Plowed under, plowed under,

his eyes and ears bereft.

Buffalo, too familiar now, graze our dreams.

Hidden in shadows: pronghorn, grizzlies, prairie dogs.

When Lewis and Clark hauled their bullboats

up the Missouri, neither they

nor their Book spoke of ecosystems.

All those wagons, plows, cattle

kicking up dust from Texas to Montana,

iron horses filled with rifles

spitting their bright death,

that mandate, revealed in the Word,

in dull syllables of lead,

to tame the land.

Grass to a horse's belly,

that rivaled a man's head.

And that invisible grass,

damp with uncountable mornings,

that lurks where we drown the wild echo.

So much fear from the sky:

fire, hail, the moon that undresses itself.

Yet in the dawn rising raw in the nostrils---

what use for history, what need

to be anything but an oracle:

our own chalk scripting paths,

giving permission to let go?

I could go on quoting entire poems from each section to show the author's prowess with metaphor and simile, to demonstrate his command of the narrative poem. But I don't want to give the whole book away. Suffice it to say there are many gems sprinkled through the book similar to the poem quoted above. Word Walker Press has produced an attractive book to showcase Ludwin's gifts. I heartily recommend it to all lovers of narrative poetry.

© Jim Doss