Winter 2009

Table of Contents - Vol. V, No. 4

Poetry Translations Non-Fiction Fiction Reviews

Dan Cuddy

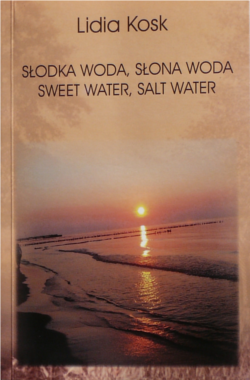

Lidia Kosk,

Słodka woda, słona woda / Sweet Water, Salt Water, translated and edited by Danuta E. Kosk-Kosicka, with three short stories translated by Wojciech Wiśniewski, Jan Wiśniewski, and Piotr Kosicki, respectively.

The most remarkable attribute of Lidia Kosk’s new book of poetry Słodka woda, słona woda / Sweet Water, Salt Water is the beauty of the poetry. True Beauty is so rare in modern or contemporary writing. This book is not pretty poetry, not a Sunday painter’s poetry. It is not really impressionist in the Monet sense. We aren’t talking about dabs of imagery and the haze of an aesthetic sensibility. Lidia Kosk’s work has an elemental beauty that is more akin to nature and inspiration than learned artifice. Now that is not to say that she isn’t an accomplished poet, because she is, but to emphasize that her poetry grows out of her heart, not imposed by detached intellect. She is a poet from a country not self-indulgent and pseudo-sophisticated. Her country, Poland, her generation, experienced World War II, Nazi occupation and then the dull grey tyranny of the Communists. Negative emotions like grief color her vision but everything in her poetry points the way out of any such suffocation. Part of her endurance may be due to religious faith, as expressed in the poem Of the City’s Spirit, and part may be due to the closeness, to the love, literally, for her native soil, but much has to do with what is in her heart. Her heart can only express itself through and as beauty for that is what it is, a natural beauty, a bloom of human nature.

The book is bi-lingual. Ms. Kosk’s daughter Danuta Kosk-Kosicka, a poet herself, translated the Polish poetry into English. The translation is more than competent; it is first rate poetry. Only one word in the whole book is just a little out of kilter with American English. In line 3 of the second poem the word “Fido’s” seems odd. Presumably it is a dog’s impassioned barking that is meant. I point this out only because every other word, phrase, poem is inspired and the translation carries the imagination of the Polish poet into American English as if the poem’s native language was English. The prose on the jacket front flap and inside the book was translated by Danuta E. Kosk-Kosicka, who also edited the book. The three short stories in Chapter IV were translated by three other individuals. Special mention should be made of Wojciech Wisniewski who translated the prose of Lily, while Ms. Kosk-Kosicka rendered the poetry in that piece into English. The book is published by ASTRA of Łódź, Poland.

There are really 3 components of the book, the English being one. There is a wealth of photography accompanying the poems and on the front and back covers. Most of the photos were taken by Lidia Kosk herself. The cover is of a sunset and ripples of gentle waves lacing the Baltic Sea shore. The back cover is of Ms Kosk by a river in the Polish countryside. Throughout the book there are other photos of tree trunks and footprints on the sand of beach. These are interesting images, but the memorable images are in the poems. The third component is the original Polish on the left hand pages facing the translation on the right.

The book is divided into four sections. The first is called Birth of the World. The poems in this section are filled with a pristine beauty almost unconscious of history. The first poem is titled “Paradise.” The human is present immediately.

of each other’s irises

they dive

the overflow distills

in the morning dew

Celestial blue

strokes the heads

of forget-me-nots

snow remnants blush

into apple blooms

the sun of summer

does not burn

the earth they stroll

the rains of autumn spare

the fruit

so they can reach for it

It is a remarkable lyric. I see of at least two ways of interpreting it. The first is the Adam and Eve scenario with the ironic mention of “The fruit”. The second is of two lovers, and the fruit then becomes not a disguised threat but a wondrous sharing. Beyond interpretation is the gorgeous imagery. Paraphrasing any of it, because it is very understandable and elemental, is like analyzing comedy in that the beauty would be bleached out of the poetry. The imagery is not intellectual. Order and precision are admirable qualities but what we have here is the bloom of a garden, not the decoration of a house.

Poem after poem in this section has this wondrous vision. Some poems occur in winter and the Fall from grace and childhood and pure romantic love is intimated but the poems affirm the miracle of it all. The beauty is tangible, not some ascetic distillation. The poem below illustrates this:

Dusk falls in the stillness of forest

around the cluster of trees and brush

and settles my thoughts

Feelings stream in

from faraway times

reveal in retiring light

shadows of cows

in the meadows of remembrance

The closeness permeates:

fur odor after a hot day

chains rattling

a human connection

Strokes of the church clock

from a faraway tower

organize time

The sensations of the present evoke the past. It is, in a sense, a very Proustian passage, though the world recalled is Old World Poland and the memories of childhood there. Is it significant that the clock is a “church clock?” Perhaps the passage of time, or the consciousness of it, expels humanity from that Paradise that began the book.

A very seemingly simple poem, I Bent to Pick Up a Lump Of Earth, closes this first section. This poem is so simple in conception but it is a haunting poem, one with great meaning. That clump of earth symbolizes her childhood and everything that she has learned and that she is. She “yearned for its company/on the long road.”

Section 2 From The Cradle of Earth contains the imperfect world that is the reality that dreams cannot shake. However, this section is not about grief and loss so much as the battle between such negative emotions and the ever present joy still available and sometimes found by the heart. The title poem explains the theme of this section succinctly.

From the Cradle of Earth

pupils follow the light of stars

on the open umbrella of outer space

beneath

the clouds mature

glow crimson with pain

from the birth of beauty and dread

the imminence of passing away

sand sifting from the hourglass

rocks the cradle of earth

Section 3 is called Only the Memory Takes Note. History, both personal and national, permeates the poetry here. In Gloria Victis the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 is shown to be the harbinger of August 1994, when Poland is truly free. Some of the history of Poland may be unfamiliar to American readers but the particulars won’t mar an appreciation of the poetry. The internet is always available to look up a strange name or an unknown event; however, the poetry may be set in history, but the poetry reverberates in the heart, in the soul. This section is both elegy and affirmation. Though Polish history has had bleak moments in Lidia Kosk’s lifetime, and though she acknowledges the sorrows, she is anything but a defeated spirit. The poems are so interwoven with the ascendency of first one emotion and then another, but a beauty and a strength prevail in her heart. Evil and pain are not glossed over but the poet transcends them, like a flower after a grueling winter. The poem below illustrates this:

you float in through the window

open on this March night

our thoughts interweave

rejoin our journey halted

by the stillness of the Styx

your arms

shield me

from the stiffening chill

stop the icicles from wounding

my heart

Section 4 is titled From the Storyteller’s Volume. It contains both prose and poetry. History and the lyric are transformed into folklore. Narrative and symbolism are the keys here. The story Lily is as beautiful as any of the poems in the book. It is on one level similar to a child’s tale but it is very much the story of a mature poet.

I’ve just given a short sketch of the book. There is much to explore, much to marvel at. Paraphrasing the title of the book, and borrowing from William Blake, I would call these poems songs of innocence and songs of experience.

© Dan Cuddy