Summer 2008

Table of Contents - Vol. IV, No. 2

Poetry Translations Non-Fiction Fiction Essays

Michael Fallon

Rediscovering Poe: the Mask and the Man

We know that Poe was born in Boston in 1809 and died in Baltimore in October 1849 of swelling of the brain. Some speculate that his death was caused by exposure or pneumonia, some by a blow to the head. Possibly, it was an unfortunate combination of all the above. That he foamed at the mouth and died of rabies, as one recent theory offers, seems a bit too perfect and over the top.1 We don’t even know for sure what Poe was doing in Baltimore, but whatever they might claim in Richmond, Philadelphia, or New York—all places where he lived at various times—he died here and we’ve got the body.

And we are lucky to have the body at all, because University of Maryland medical students might have dug it up and stole it—as they were in the habit of doing to freshly buried corpses in those days. Westminster graveyard was as close then as it is now to the University of Maryland Medical School. It was then the old Western Burying Ground (the Presbyterian church at the site was not built until 1852) and fresh bodies were needed for dissection to help the future doctors learn human anatomy and future dentists to study human teeth, that, after all, were not really needed in the tomb (or so one hopes). All that the grave robbers had to do was peer over the wall of the graveyard and look for the upturned earth that marked a recent burial. That night, neighbors might have heard the clatter of a shovel against stony ground or the hollow thump as a pick struck the coffin. A passerby might have noticed the dim arc of a swinging lantern, the hushed voices. The next day, mourners at a funeral might have found an open grave and a fresh mound of earth, the newly bereaved wife swooning into the arms of the minister. Poe would have appreciated this. His characters find more ways to escape from coffins than Harry Houdini.

Poe was half Irish, enough for him to have inherited the Irish propensity for good and bad luck. He arrived in Baltimore around a week before his death, got off a boat from Richmond and disappeared into the city known as Mobtown during an election campaign. Needless to say, elections were a lot more exciting in those days since free drinks could be had in many of the taverns, and roving gangs went looking for voters who had already had a few and plied them with more drink to vote them as “repeaters.” The gang would herd them to various polling places and have them vote as many times as possible in different sets of clothes. One theory is that Poe was the victim of one of these gangs. Certainly he was found on the rainy afternoon of October 3, 1849 by a printer named Walker delirious and semi-conscious on the sidewalk outside a tavern that was a polling place on East Lombard Street. Probably drunk, he had likely been out for some time on that damp afternoon and might have fallen into the gutter or have been struck in the head as he was shuffled between polling places. An old acquaintance, Dr. J. E. Snodgrass, editor of the Baltimore Saturday Visiter, summoned to the scene, said later that he found him slumped in an armchair in the bar. Poe died in a hospital four days later. Well, all this was the bad luck.2 The good luck being that Poe was buried in Baltimore and no one has stolen his body. Yet.

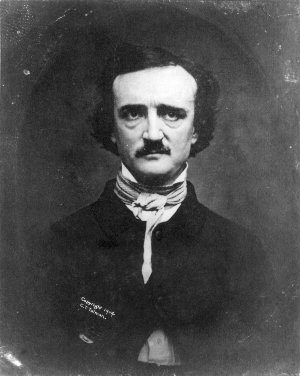

Edgar Allan Poe photographed in 1848, the year before his death

How Poe actually spent his week and why he came to the Monumental City in the first place is the subject of a movie, a novel, and much historical detective work and debate.

Poe had a hard life, one he made harder by being a genius and knowing it. He had strong literary opinions and a keen sense of what would engage, thrill and even outrage an audience. In the short story, Berenice, Poe has the bereaved husband open the coffin of his recently deceased wife and while in a trance, pull out all her teeth. The poor fellow was that obsessed with his wife’s smile. But you’ve guessed by now that Berenice really wasn’t dead and that her entranced husband ignored all her shrieks. Poe knew that outrage and controversy sold well and he proved himself right again and again: the circulation of every magazine that he edited and in which he ran his work dramatically increased. He was a quarrelsome fellow which led to many bitter arguments with editors and the magazine owners he worked for, either over editorial policy or his heavy drinking. He was a bit of a prankster and enjoyed making fun of those that he did not like or respect, which turned out to be a lot of people, including his rich stepfather, Richmond tobacco merchant John Allan, who disowned him, and many of the prominent writers of his time. All of this trouble led to money problems. Poe struggled all of his life to clothe, feed and house himself, along with his wife (and cousin) Virginia and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Maria Clemm. He once turned down a dinner invitation from John Pendleton Kennedy, a prominent Baltimore editor and writer, because he felt his clothes were too shabby to be seen in such company.

As if all this weren’t trouble enough, Poe had to watch many of those he loved slowly sicken and die. Tuberculosis was extremely common in Poe’s day, and there was no cure for it. Those who had it, including his wife Virginia, died slowly, grew paler and paler, like many of Poe’s characters. They had violent coughing fits, frequently bringing up blood which stained their handkerchiefs and spotted their clothes. It usually took years for them to die. Sometimes a remission would inspire temporary hope and for a few weeks or months, color would return to the cheeks, but the end was always the same: they grew translucently pale—considered a kind of transcendent, romantic, pre-death radiance in Poe’s day—and died. In the 19th century, tuberculosis was called consumption and it was thought of as the romantic disease. Poe watched helplessly as it killed Virginia, and very likely he had a touch of it himself.

Nearly everyone knows something about Poe, yet he is one of those shadowy, enigmatic figures who seem to dissolve into darkness the closer you look. Growing up in Baltimore, I remember reading The Raven, To Helen, and Annabel Lee in grammar school and always dimly associating Poe with Halloween. I think there were even a few Poe masks back then in the Ben Franklin Five and Dime—rubbery and empty eyed, suspended by fishing line from the ceiling in a long row with the goblins, witches, and Frankensteins. With the broad, pale forehead, the small chin, the bottle-brush mustache, the troubled eyes with half moons of shadow beneath them—all framed in a nest of black hair the color of crow feathers—Poe had a remarkable and interesting face, a look of troubled intensity. When one examines his photograph on the cover of the Modern Library edition of his collected works,3 it is hard not to wonder about the nature of the mysterious storms behind the prick of light in the eyes. Yet the mask we think we know is the enemy of the mysterious presence that speaks to us.

These days, we often treat Poe as a comic figure, a sad eyed, ghoulish clown dressed in black with a loud, villainous laugh. We do this, of course, to keep the real horror in Poe at a distance because Poe the poet and writer is dangerous. His insights into human character are both disturbing and illuminating. It is the troubling, darkly ironic Poe, the one who understood the struggle of man against himself, that is the real presence beyond the mask.

The imagination is an inspiring but haunted place, and anyone who lives by it is bound to be erratic and troubled at times. Poe lived and wrote on the edge. He was interested in the borders between life and death and in the nature of life and death themselves. Poe believed in reason up to a point, but more in intuition and imagination, more in dreams than in science or facts, as he makes clear in his manifesto, Eureka. There is in Poe’s stories an eerie sense that the borders between life and death are permeable. His corpses do not stay dead. They struggle in their coffins, throw off the lid, rise up in their grave clothes, and silently climb the stairs out of the vault and into the darkly lit bedroom, or they speak to us from some vague beyond out of mouths and tongues stiff with rigor mortis.

Of course, we cannot know the man, but we can listen to his voice, or rather to his voices. It is the way his narrators tell us their stories that seems to me one of the things that is most fascinating about reading Poe. I view as his best stories The Cask of Amontillado, The Tell-Tale Heart, and The Black Cat—and all three tales are told by madmen. All protest that they are not mad, but supremely clever and rational. All give us their justifications for the murders they commit, but the murderers do not know why they have murdered. In The Cask of Amontillado, Montresor never tells us what Fortunato supposedly did to him. How could it possibly have been anything so terrible as to justify being walled up in a tomb alive? The very nature of Montresor’s revenge gives the lie to his sanity. We do not know, as he narrates his tale, if he is confessing or bragging about his crime (or some combination of the two). In The Tell-Tale Heart, it is supposedly the evil eye of the innocent old man that motivates the murderer, and in The Black Cat, it is supposedly the cat that torments the narrator and causes him to kill his wife. But in each of these stories, the voice undermines itself. And thus reason and the rational mind are overthrown, and we are left to wonder how well we understand our own motives, our reason untethered, driven by motives we do not understand or cannot admit to ourselves. In The Black Cat and in The Tell-Tale Heart, the narrator is blind to himself and must destroy the eye that he fears sees him truly—in the one-eyed black cat and in the pale blue cataract of the half-blind old man, he sees at once the eye of judgment and his own evil reflected back to him. It is the apparent blindness of reason itself that is most often the real horror in Poe.4

It is likely that Poe experienced the conflict between the rational and irrational because he was a man often at odds with himself. If one reads, for instance, Poe’s explanation about how and why he wrote The Raven, he makes too much sense. He sounds very much like one of his own unreliable narrators. He lays out the reasons for all the decisions he made as he wrote The Raven, down to the effects he wanted and his choice of subject matter. We want to ask, why then, Edgar, do you consistently choose terror and horror as your subject matter when they are only a slice of all the possible subjects that might enthrall an audience? Can anyone believe that Poe was simply interested in horror because he knew it would sell? A writer’s subject matter chooses him as much as he chooses it. It would have taken a kind of blindness for Poe to believe he had thoroughly accounted for the imaginative process by which The Raven came into being. Strangely, as is obvious from his stories, Poe himself understood well that the more we are blind to our own conflicts, the more power they have over us.

In his own life, Poe was a master at undermining himself, drinking himself out of numerous jobs, offending people he could not afford to offend, and finally appointing a man who hated him as his literary executor. How did he explain his own actions to himself? It is possible that the narrative voice we see in so many stories was as much a product of Poe’s own internal conflicts as it was a result of clever story telling. It is likely that the core of creativity itself is conflict. Certainly anyone with a powerful imagination must experience a conflict between the life that is and the life that can be imagined, and as cause or effect, conflict with others and within the self. Robert Graves claims in The White Goddess that a poet’s fate is determined by the struggle between himself and his Weird, that darker brother (or sister) with whom he (or she) must wrestle in order to make his art, a shadow self formed of repressed desires and unrealized possibilities. (As a man adds a brick to the top of a wall, his Weird pulls one out from the bottom.) Poe knew his darker brother well. He was a lover of the double vision that is irony, and I have no doubt that he must have often smiled sardonically at himself.

At any rate, I recommend reading the above mentioned stories out loud by candlelight or firelight. While they are terrifying in their way, they are also beautifully written and often darkly funny as we listen to the narrator accomplish his revenge or slowly weave the web in which he, himself, will be caught.

Poe believed in an afterlife—where that which we call spirit returned to a kind of universal mind after death. He had no rational proof for this, but only what he could sense with his intuition and imagination. Yet Poe could be quite the rationalist as we see in his character, Auguste Dupin. In Murders in the Rue Morgue and in The Mystery of Marie Roget, Dupin uses both inductive and deductive reasoning but finally relies on a leap of the imagination to solve his cases. The admiring narrator in the two stories chronicles the progress of Dupin’s genius, which prefigures Holmes and Watson, and all the other standard pairs of detectives, where one is an eccentric genius and the other a kind of Everyman who records the case. The Everyman, a stand-in for the reader, is astonished as the genius proceeds, through various mental acrobatics, to solve the most complex cases while sitting in an armchair in the dark as if he were an oracle speaking from the other side of death.

There are those who believe the door is shut after death and no light comes out from around the jamb. They are blind to the strange intimations that come to the powerfully imaginative from time to time, that whatever consciousness is, it is something that is capable of imagining worlds, infinities, and it is afloat like a bubble in an incomprehensible vastness where reason becomes lost. As he makes clear in Eureka and elsewhere, Poe believed that the nature of reality or truth was revealed more profoundly in our deepest dreaming than in science or reason. He would have been appalled by what is today is called “scientism”, the belief that the only valid knowledge is that which can be acquired through the use of the scientific method. These days we like our certainties and we would prefer to be stunted than troubled, so far as to believe that all of human history and the imaginative and artistic accomplishments of human beings, and thus, even science itself, can be reduced to a series of electro-chemical reactions, localized in a few ignorant nerve cells. (But listen how, with every synapse, they doth protest.) It is the tragedy of our age that, having given up on God and the angels, we cannot imagine humanity as anything more than biologically efficient machines.

You think I confuse Poe’s ideas too much with my own? I swear he sat across from me one night at the Cat’s Eye Pub in Fell’s Point, Baltimore, an hour or so before closing, holding forth on how the imagination is an echo of the universal mind and the vital link between the living and the dead. I’ve seen his silhouette emerge suddenly from the dark on more than one occasion, snow falling all about us.

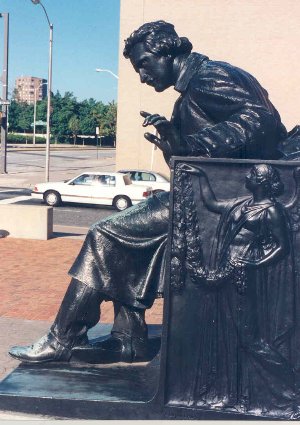

Originally, the seated statue of Poe by Sir Moses Ezekiel that is now located in the plaza in front of the University of Baltimore School of Law5 on Mount Royal Avenue, stood elsewhere. Some forty years ago, it was still situated just south of Wyman Park on the small, roughly triangular island that separates 29th Street from Art Museum Drive, not far from the impressive double equestrian statue of Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. While the Confederate generals on horseback are about the height of bigger than average dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, the Poe statue, while truly a nice work of sculpture, is about the size of a preadolescent boy in comparison, and in that location, it was almost entirely hidden by trees and untrimmed shrubs. A like-minded friend and I would go occasionally to have a drink with Edgar, and I remember watching the snowflakes fall out of the sodium vapor-lit sky, about his black shoulders and the dark of his head. One interesting thing about the statue is, that as you approach it, it first appears that Poe’s eyes are closed and that he is asleep or in a state of reverie, but as you get close enough to look into them, you notice the eyes are, in fact—Open—and staring intensely straight ahead. Here are two of Poe’s paradoxical faces: the romantic dreamer, and the lover of clear-eyed reason.

A recent photograph of the Poe statue in Baltimore by Christopher T. George

The lonely gays that used to cruise Art Museum Drive in those days might have known Poe was there but not many others. I loved the weedy charm of the spot and the echo of irony when I quoted the line from The Raven inscribed on the cement base of the statue, Dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before. It said so much about the elegant ruin of my beloved city. Now that Edgar’s statue has been relocated to its present much more dignified and public location in front of U. of B.’s Law School, I hope it has inspired a few lawyers to take a vacation or startled a few undergraduates as they zig or zag across the plaza at 3 in the morning.

It would be appropriate on the bicentennial of Poe’s birth, coming up on January 19, 2009, if the city rang it in with a tintinnabulation6, a city-wide ringing of church bells, maybe in combination with a chorus of car alarms and jackhammers. I hope by then, that my fellow Baltimoreans will have been tempted to take another look at the work, the man, and the city that holds him in its concrete embrace.

Poe was a grab bag of contradictions. He was a romantic dreamer of opium dreams, a rationalist inventor of the detective story, a hard drinking, quarrelsome hoaxer; a philosopher, critic, poet, story teller, and visionary—and is now an illustrious and permanent resident of Baltimore City, which, with the help of pennies donated by Baltimore school children, built a marble monument over his grave, supported by several slabs of poured cement to make sure Poe never got restless and always felt at home. Everyone in Baltimore can take pride in this, whether a permanent resident or just visiting: something about which one can never be quite certain.7

![]()

1 “Edgar Allan Poe Mystery,” University of Maryland Medical Center 2006 News Releases. July 2007.

2 Joseph Evans Snodgrass, “The Facts of Poe’s Death and Burial,” Beadle’s Monthly, May 1867, pp. 283-287, available on the

Poe Society of Baltimore website.

3 Edgar Allan Poe, Poe: Poetry, Tales, and Selected Essays. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1996.

4 Edward H. Davidson, Poe: A Critical Study. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1964, p. 151 cited in Christopher Marchsteiner, “The Unreliable Narrator and ‘The Tell -Tale Heart.’” Research Paper. University of Maryland Baltimore County, February 2007, p. 5.

5 Mr. Alexander G. Rose, a former head of the Poe Society and Professor of English at the University of Baltimore (who taught me there in the late 60’s and early 70’s) and also a friend and neighbor of mine for many years, was instrumental in having the statue moved to the plaza outside of U. of B. Law School, a place where it finally gets the attention and respect it deserves.

6 A word Poe invented and included in his poem, The Bells.

7 I want to acknowledge Joby Taylor, my co-instructor at University of Maryland Baltimore County for his insights and comments and the students of Humanities 121 for their research essays and the lively class discussions that helped inspire this essay.

© Michael Fallon